There are many resources for learning music notation, both in print and online. This article won’t attempt to duplicate those, but instead focus on challenges and confusion handbell musicians may experience. Ringers with little or no prior music reading background may want to work through a workbook. I especially like Alfred’s Essentials of Music Theory – Complete. Note the catalog number (16486 – book with 2 listening CDs), as Alfred has several similar products. It’s an inexpensive resource. Though the book is available without CDs, ear training will help ringers improve. Ringers can start wherever the book presents new information, on page 1 for some, perhaps a few chapters into the book for others, and work through the book as far as the director suggests.

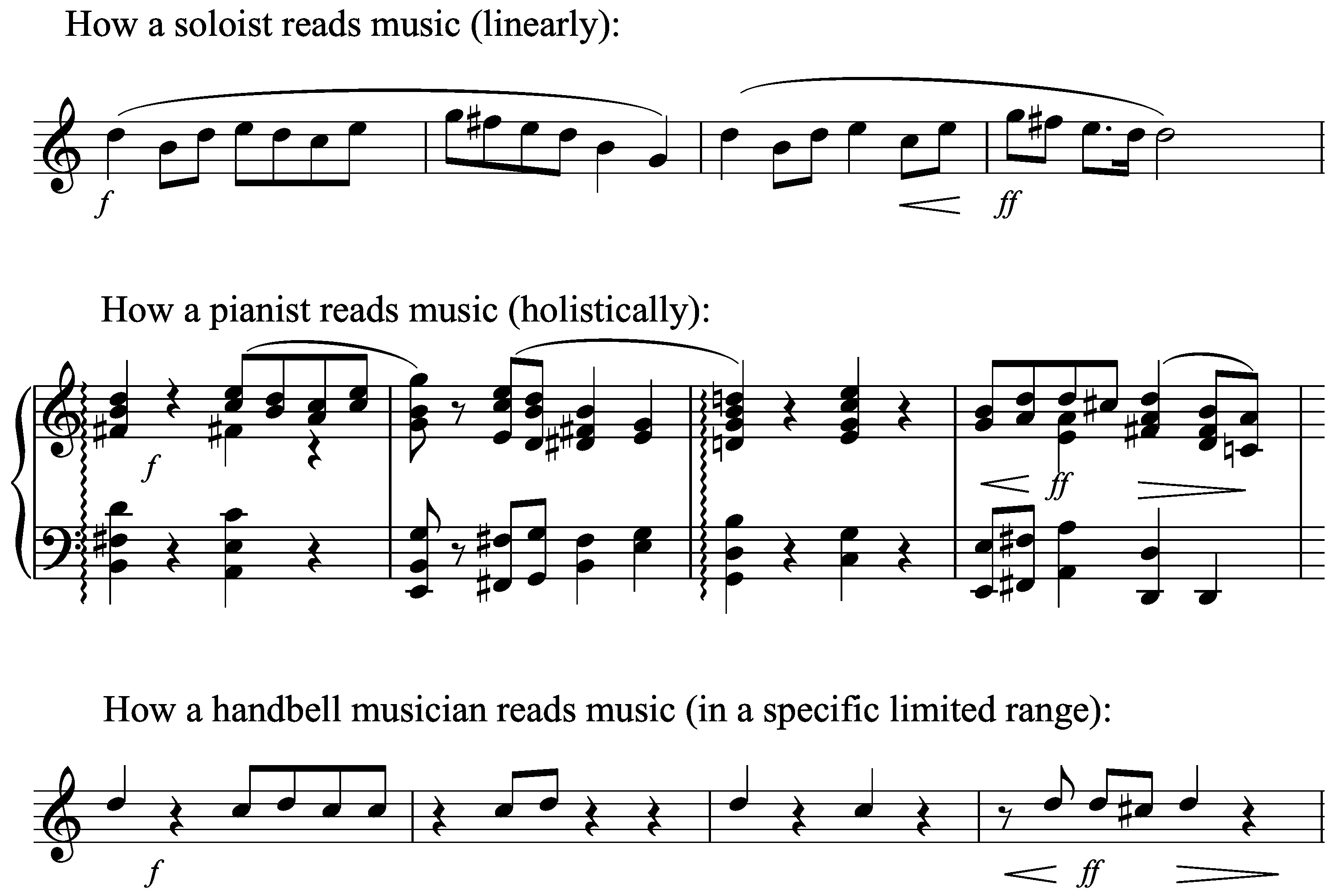

Even if someone reads music well, handbell music isn’t like a solo instrument where you play a single musical line, nor like piano where you play everything written.

The standard handbell assignment is two adjacent natural notes with related sharps and flats. Example: C6 D6, which includes C#6, Db6 (the same physical bell as C#6) and D#6. D#6 is the same bell as Eb6, but when Eb6 appears in the music, the person playing E6 is responsible for it. So a ringer is playing bits and pieces of melody and accompaniment in a narrow pitch range. That can be hard to track at first, even for someone who already reads music. Remind ringers that the beats line up vertically. They can discern the rhythm in the overall pattern, then find their individual part in it.

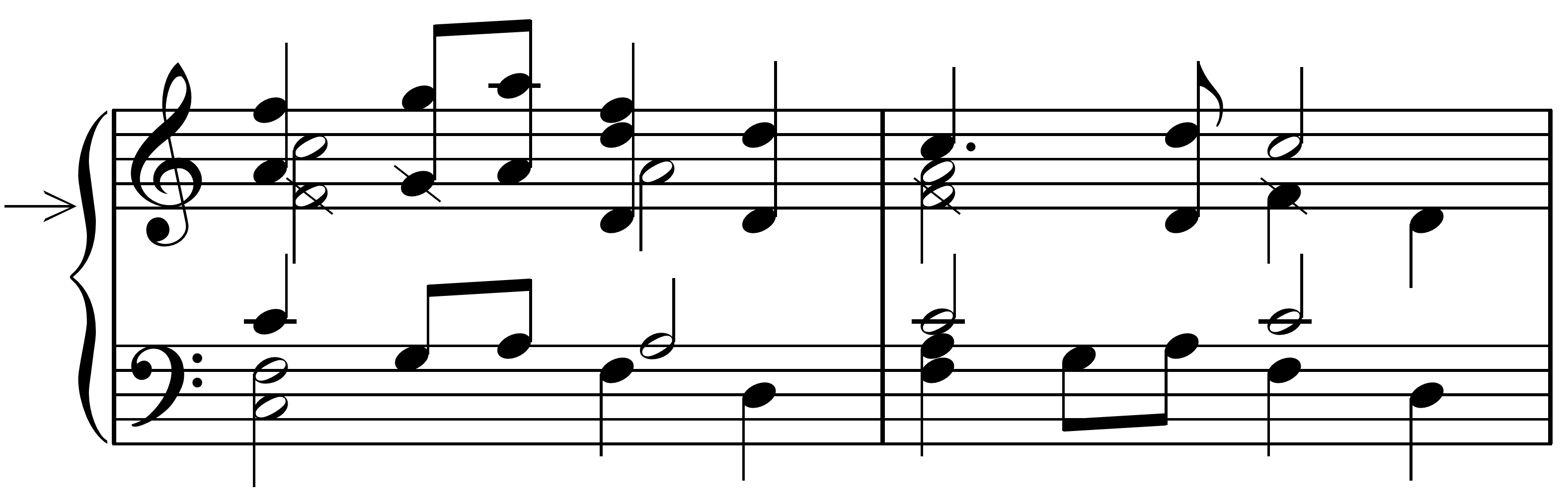

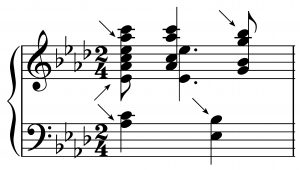

Moreover, handbell musicians don’t see rests everywhere another instrumentalist would. Instead, rests for one bell are implied in notes for other bells. Below, the arrow points to crossed-out notes representing one person’s assignment (F5 G5). Notice the absence of rests.

Stem direction: Stem direction is critically important so handbell musicians know not only what part of the music they’re playing (melody? accompaniment?), but what techniques (like mallets) apply to them. Moreover, flags on the stem communicate note values. Struggling ringers sometimes focus so hard on tracking note heads (to play the correct bell) that they miss information contained in the stems. Encourage them to read the entire note. Also realize that struggling and new ringers can’t remember which note to play in the right hand, and which in the left. If you’re using standard assignments in a 3 octave choir, every ringer holds the lower bell in the left hand, and its note falls on a space. The right hand holds the higher bell, whose note falls on a line. Left hand space, right hand line. That may free up some brainwaves to read note stems.

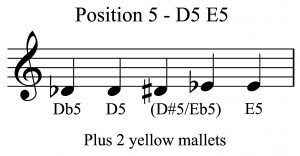

Setup notes:

I like to create an index card with the above information for each position. You can spread them out on the bell table so ringers learn which bells (and other equipment) belong at each station. Otherwise, inexperienced ringers tend to set bells out in a jumble, or place similar pitches from different octaves together (e.g. C6 next to C5). The card also helps teach ringers which notes that position is responsible for, and what other equipment (mallets, chimes) they should have before rehearsal starts. As an aside, D5 E5 is an excellent position to reserve for beginning ringers. I’ll discuss assignments later in this series.

Key signatures: Ringers often get lost at key changes, because (to a struggling ringer) a key signature looks like this:

Imagine if you had to decipher a key signature like that, which makes no sense. An experienced music reader looks for a recognizable pattern, but it all looks random to struggling ringers. By the time they figure it out, they’re lost.

Another problem is that key signatures appear in a specific place on the staff, which may not be where an individual ringer is reading.

The arrows point to notes affected by flats in the key signatures, besides notes falling on the actual lines and spaces of the key signature, but a struggling ringer won’t realize that. S/he is reading with tunnel vision, and without enough fluency in the staff to recognize that flatting the A5 also means flatting the A6, for example, or even to recognize pitches an octave apart. Ask the ringer to write “Ab6” close to where s/he’s reading.

Many directors try to teach ringers the names of key signatures, like F major. For a struggling ringer, it’s too much information, and not especially helpful. It’s far more important to know which sharps and flats they need in their hands (Bb, in F major).

I rang for several years (and struggled to understand the circle of fifths) before anyone pointed out that flats and sharps occur in a predictable order. Meanwhile, I would puzzle out key signatures note by note, invoking Every Good Boy Does Fine, because of course I didn’t read the staff fluently.

If ringers learn the following rules, they can quickly count the number of sharps or flats in the key signature and know what bells they need:

Sharps:

1 = F

2 = F, C

3 = F, C, G

Flats:

1 = B

2 = B, E

3 = B, E, A

4 = B, E, A, D

Other key signatures exist, of course, but the above rules cover the key signatures an unauditioned handbell choir will play most often. A ringer could make a flashcard and memorize the information, noting that 4 flats spell a word, BEAD. Or a ringer at, say D5 E5, could just remember, “If I see 2 or more flats, change my E bell. If I see 4 or more flats, change both my D and E bells. Ignore sharps unless applied directly to my note, or more than 3 appear in the key signature.” But make sure the ringer also sees the list above, or the information s/he’s asked to memorize will still seem random and arbitrary.

Also teach ringers how to read the difference between pitches in the key signature and accidentals (sharps, flats, or natural signs not in the current key signature). If an accidental appears near the clef, it looks (to the uninitiated) like it’s in the key signature.

Modulation: I never knew about modulation until I took piano lessons. That’s unfortunate, since it’s common in handbell music, as the composer moves the melody around to different parts of the bell choir.

Modulation is a transition from one key signature to the next. Not all the bells change at once (and some don’t change at all). If your notes have accidentals during the measures before a new key signature, the music is preparing you for the change. Therefore, if you change bells to play accidentals, you don’t need to change them again when you arrive at the new key signature; they’re already in your hands.

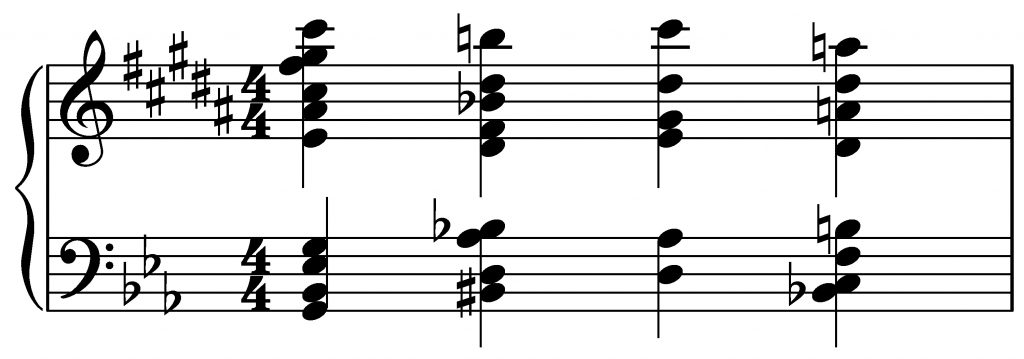

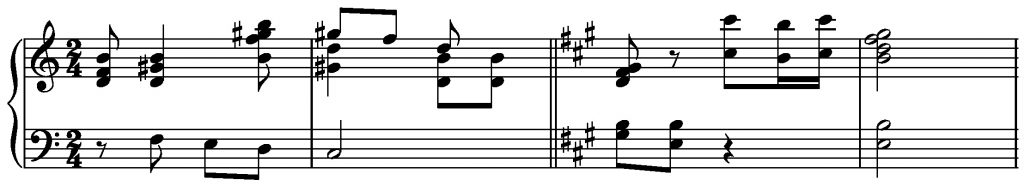

Not realizing this, I would try to puzzle it out. Instead of understanding modulation as a whole, I would decipher accidentals and then the new key signature separately, one note at a time, Every Good Boy Does Fine, rapidly falling behind. It looked like this to me:

Here’s an example more typical of handbell modulation:

Notice there are no sharps in the first key signature. Look at the G# accidentals (hint – all the sharps are on G in the first two measures here). They prepare for the new key signature, which contains G#. If you’re playing a G, you pick up G# in the first measure shown (or prepare beforehand), and keep it. In the example above, not all the sharps in the new key signature appear in the modulation; F# and C# begin at the same time as the new key signature. If you’re playing either of those bells, you put it down the last time you use it and pick up the new bell to prepare for the key change.

I was always surprised when an accidental repeated in subsequent measures of the transition, as you see above, though this is normal. An accidental continues through the current measure (also called a bar), but the bar line (i.e., the end of the measure) cancels it. The composer writes the accidental again to set up the transition gradually and consistently over a number of measures, not dashing back and forth between bells.

Similar but not the same: We have numerous concepts in music that seem like the same thing, but they aren’t always identical. It can be hard to implement them correctly when you don’t really understand what they mean. Explain to ringers how the terms are similar, how they differ, and how to move the bell. Also translate terms for them and explain why some words are in Italian (because Italy was the center of Western art and culture when these terms first appeared, and many important Baroque and Renaissance composers were Italian). I feel fortunate that, having studied in Rome, I spoke Italian before I learned to read music, but not every struggling ringer has that advantage. Encourage ringers to buy a music dictionary or to consult one online.

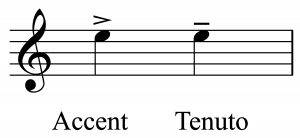

Example: Accent, sforzando, and tenuto are all ways to emphasize a note. A stress accent (>) makes a note louder in the context of the dynamic (overall loudness). You can have an accent on a note in a mezzo-piano section, and it’s just a little louder. You would ring your bell with a bit more power so it stands out from the surrounding notes. Sforzando (suddenly forceful, abbreviated sfz) means to play suddenly as loud as possible. Sforzando is followed by subito piano (suddenly quiet – accomplished by a brush damp), then crescendo (getting louder), generally to forte (loud) or fortissimo (really loud), often while shaking bells. This is all done on the same note (usually a whole note or longer), not subsequent notes.

Tenuto (literally ‘held’) can have different meanings depending on context. Usually it means to give the note a little more weight (lean into the ringing stroke), and/or to hold the note for its full value (don’t damp early, maybe damp a little late). Tenuto (when written as a word, sometimes abbreviated ten.) means the same as a tenuto mark over the corresponding notes. In handbells, we tend to see tenuto written instead of notated with a line, perhaps because chords are so dense a line might be overlooked, or misread as a ledger line.

A struggling ringer may confuse staccato with these other articulations, though staccato doesn’t emphasize a note. It merely means the note is played crisply, not connected smoothly to other notes (which would be legato). In handbells, staccato notes usually involve a technique like mallets, plucking, or martellato.

Directors, to encourage the sound you’re looking for, use movement terms like “slash” for accent, “punch” for sforzando, and “press” for tenuto.

Another point of confusion: the distinctions among ritardando, rallantando, broaden, meno mosso, and fermata. All can mean the music is slowing down.

• Generally ritardando (gradually slowing down) is followed by a tempo, which means return to the tempo (speed) you were playing before you slowed down.

• Rallantando is synonymous with ritardando.

• When you see broaden, it means slow down and stay there.

• Meno mosso (less movement) means play at a slower tempo immediately.

• A fermata (literally ‘closed’), also called a bird’s eye, means hold the note (keep the bell moving) until the director signals to move on.

Other sources of confusion:

• Which symbols apply to a note – example: articulation like an accent or staccato

• Which symbols apply to a measure – example: an accidental continues to the end of the measure

• Which symbols apply until explicitly cancelled – examples: LV, dynamic marking, time signature, key signature – all these carry over the bar line

• Why there is no “m” dynamic – “m” stands for mezzo, a qualifier that means “medium.” We speak of sound as being loud or soft, in varying degrees; we don’t speak of sound as “medium” like a shirt size. If composers need a ‘neutral’ dynamic, they generally write mezzo-forte (medium loud).

• Why a piece doesn’t always start on beat one – pickup notes allow a composer to place the rhythmic emphasis (especially the pulse associated with beat one) somewhere besides the beginning of the musical line.

• That music can crescendo (grow louder) and decrescendo (grow softer) without changing dynamic levels – A struggling ringer may ask the director, “How loud are we supposed to get?” The answer: “You’re still mezzo-forte.” Sometimes music needs a very slight increase in volume to convey its full meaning, just as you can speak louder without necessarily shouting.

• The differences between key signatures and chords – for example, why is there a Bb in an F major key signature, but not in an F major chord (triad)? This puzzles your struggling ringer, who didn’t learn scales and triads on the piano, especially when you speak of “F major” without drawing distinctions.

Conflicting note values: Sometimes a ringer will play a whole note with a bell, then later in the same measure, play another note with the same bell, perhaps a quarter note on beat 3. This confuses ringers, who assume music is written from their individual perspective. Instead, music is written from a global perspective. It would look strange and be hard to read otherwise. The same bell can be both part of a chord (the whole note) and part of a musical line, perhaps the melody (the quarter note). They would re-ring the bell at the quarter note, with damping at the director’s discretion, depending on whether you still need that note in the chord or you want the melody cleanly damped.

About brackets: The economics of handbell publishing (the market is significantly smaller than for choral works) demand that publishers to get as much mileage as possible from a single version. Instead of publishing separate versions for 3, 4, and 5 octave choirs, they edit the music so it can be played by groups of various sizes. To avoid a 3 octave choir starting a musical line they can’t finish (because it extends into a range of bells they don’t own), composers put certain notes in brackets or parentheses. The work contains a footnote explaining which size choir omits notes in which type of brackets, usually (), [], or <>. Another reason: the composer might prefer that a bass note be played on, say, C3 if available, otherwise on C4. This would be written with C4 in brackets for a 5 octave choir (which plays it on C3 instead). A 3 octave choir, having no C3, plays the note on C4.

About interpreting high treble parts: A ringer who’s struggling isn’t a good candidate for a four-in-hand part, but someone in the treble section may be confused by all the markings; conventions vary depending on the publisher and the situation. Sometimes, when the 4th and 5th octave treble bells (C#7-C8) come in, a line appears above the top notes with Coll’ 8 (‘with the octave’), and a footnote on the page tells you how to interpret it. The two most common situations: double all the stems-up notes, or double only the top note. More rarely, you might play some notes one octave higher, without doubling. This is notated 8va (ottava, or octave). Always read the footnote to ensure you’re interpreting Coll’ 8 and 8va as the composer intended. Other times, 4th and 5th octave notes are written in for clarity or because of editorial policy.

A situation to watch out for is when most of the treble section is Shelley ringing with their own bells in octaves, but certain ringers have bells that double someone else’s notes. For example, C6 and C7 are commonly assigned to two different people. If C6 is supposed to be doubled, you may have to point it out to the person holding the C7 bell.

Also note that piano music uses 8va (ottava) to indicate an octave higher in the treble and an octave lower in the bass. Handbell music often uses 8vb (ottava bassa) in the bass.

This isn’t an exhaustive list of music reading challenges, but it gives you an idea of the kinds of issues that trip a struggling ringer, or at least this former struggling ringer. Next time, I’ll talk about marking music.

Copyright © 2014 Nancy Kirkner, handbells.com